The question of how we will inhabit cities after COVID-19 has popped amongst most urban planners, as we all question urban dynamics and see the pandemic as an opportunity to reshape not only the way we inhabit cities, but also how we move in them.

Since the first images from an isolated Wuhan to the photos of empty streets in New York, the media have shared powerful images that invite urban enthusiasts to question the use of street space generally dominated by cars.

The disruption of our everyday lives brought a perfect momentum for urbanists to push forward a sustainable mobility agenda as many people worked from home, micro-mobility became the only type of mobility for many, and even the World Health Organisation encouraged people to consider riding bikes and walking whenever feasible.

Since public transportation and cab services are still considered risky spaces for infection, local governments decided to pedestrianise streets and broaden bike lanes in cities such as New York, Berlin, Milan, Bogota, Barcelona, Mexico City, Paris, Vienna, Sydney and Brussels.

Planners and local governments have described it as a moment for mobility to change, an approach that is still to be tested once the social distancing restrictions are lifted, and the use of walking and biking is tested versus motorised transportation such as motorbikes and cars.

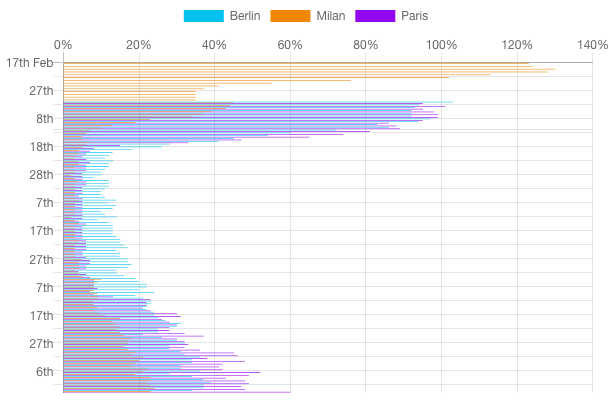

Car affluence dropped to almost 40% in most major cities; some cities adopted temporary measures implementing pop-up bike lanes while others fast-tracked bike paths scheduled in the pre-corona city planning.

City mobility adapting to a health crisis

One of the most relevant examples of city mobility adapted to the health crisis is Paris. The region plans to invest 300 million euros in building 650 kilometres of pop-up and pre-planned cycleway infrastructure. In an overnight operation street workers blocked traffic and painted bike icons turning streets into safe streets for biking.

Coronavirus lockdown and the decrease in car traffic accelerated the implementation of the “Plan Vélo” which is part of major Anne Hidalgo’s promise to turn every street in Paris cycle-friendly by 2024.

Berlin introduced 20 kilometres of pop-up bike lanes, as Berlin Roads and Parks Department official Felix Weisbrich called this a “pandemic-resilient infrastructure.” As the pandemic has accelerated the discussions in districts and municipal parliaments, public officials can push for urban infrastructure to be implemented ata faster speed than what the bouroucratic procedure would usually take.

Pop-up bike lane in Kottbusser Damm, Berlin. Source: author

The city of Milan implemented the “Strade Aperte” plan which contemplated the transformation of 35 kilometres of city streets into either pedestrian or cyclists roads. The Italian government issued bike-friendly traffic rules and promised people in bigger cities to provide a subsidy of up to 60 per cent of the price for the purchase of bicycles and e-scooters, up to a maximum of 500 euros.

Brussels planned to build a total of 40 kilometers of new cycle lanes. While the British government announced an emergency plan of 250 million pounds to set up pop-up bike lanes, safer junctions and cycle-only corridors.

Finally, Bogotá is one of the cities with the largest pop-up cycling lanes expansion during the pandemic crisis as the city implemented 80km of temporary in-street bikeways to supplement 550 km existing bike paths.

The pop-up infrastructure like removable tape and mobile signs not only makes it easier for people riding bikes to keep self-distancing, but it also encourages people who would not cycle regularly to explore new ways of transportation in a more comfortable space.

What about cars?

The adaptation to COVID-19 is not always sustainable and resilient. The sanitary measures present a risk as cars represent a tool for isolated mobility. Car-centric cities may continue to be so as car use increases.

As there is a higher demand for activities to restart under social distancing conditions, many cities in Europe started embracing drive-in culture not only for food but also for churches, cinemas and even concerts.

Examples of drive-in entertainment alternatives take place in the outskirts of cities as it is the case in Lithuania and Denmark. German car cinemas became popular near Cologne, and the city of Schüttorf close to the border of Germany and the Netherlands hosted a party in a drive-in club where the performer invited people to “honk if they were having a good time”.

In the United States, famous for its drive-in culture, a strip club continued operation under this new modality that would allow people to keep distance as the attendees stayed inside their cars.

While drive-ins help entertainment industries to cope with the closures imposed by the sanitary restrictions, there is a risk, especially in the suburbs, to develop an even more motorised culture and a lifestyle that is more dependable on cars.

What can urban planning learn from past epidemics?

One of the first examples of a city adapting to an epidemic is the cholera outbreak mapped by John Snow which encouraged cities to establish higher hygiene standards and prompted the relevance of statistical data in city planning.

However, more recent outbreaks like the case of SARS epidemic that affected cities in China, South East Asia and Canada highlighted the vulnerability of dense cities to become arenas for a fast spread of the virus. Although the use of public transportation was reduced in cities like Taipei, -the daily ridership of public transportation decreased to 50% during the peak of the 2003 SARS period– there is no significant evidence of a shift toward sustainable transportation. The SARS epidemic provided more examples of social control and exceptionalism than examples of sustainable transportation.

In the case of Covid-19, even if urbanists hope for the outbreak to be a significant opportunity to design more sustainable cities in the “new normality”, and car sales have drastically dropped, there is hope in the car industry for sales to rise once the distance regulations are eased since people will opt for a car to comply with social distancing rules.

In Korea and China the fears of contracting the Coronavirus have already shown an increase in the sales of cars and in the United States, according to the IBM study on Consumer Behavior Alterations, “More than 20 percent of respondents who regularly used buses, subways or trains now said they no longer would, and another 28 percent said they will likely use public transportation less often.”.

In addition, they claim that “more than 17 percent of people surveyed said that they intend to use their personal vehicle more as a result of COVID-19, with approximately 1 in 4 saying they will use it as their exclusive mode of transportation going forward.” .

In this matter, public transportation might be the most affected in terms of revenue, New York City metro system reported its worst financial crisis as their ridership decreased by 90%, while London Underground put one quarter of its staff in furlough as it has only been used at a 5% of its capacity for the past months. Even after the social distancing measures are eased, public transport might be considered more hazardous than other means of transportation and be the most affected financially.

Can city mobility restart in a resilient way?

After the biggest part of the crisis has passed and we will inhabit cities with eased sanitary restrictions is still uncertain whether mobility patterns will be affected in a permanent way. Further data will show if the coronavirus pandemic did encourage the creation of instruments for the implementations of sustainable mobility or it perpetuated a car centered approach.

So far, at a medium-term, the relevance of longer-trips has been questioned, and work from home acquired significance as an alternative to commutes. Trips are expected to be carried out mostly by walking, cycling and driving a personal car and the investment in cycling infrastructure will remain as a long-term outcome of this pandemic.

A woman biking through Schillingbrücke in Berlin. Source: author.

The learning outcomes of this experience can also have a long-term impact as they will be documented in guidelines and the experience will set a precedent for critical and resilient responses for local governments. For instance, the guide for temporary bike lanes titled “Making a safe space for cycling in 10 days”, developed by the consultancy Mobicon, delineates what should the first relevant action should include to keep safe distance while boosting more sustainable commutes.

The restoration of activities in dense cities might not bring an automatic radical change in mobility behaviour and policy but, despite the circumstances, life under social distancing became an actual experimental period that many urbanists have dreamed of and many citizens had not experimented before.

The relevant question now is whether we will be able to maintain partially closed streets and broader bike lanes after lockdown restrictions are lifted once cities get through this moment, hoping for planners, public officials and citizens to recognise the perks of having more room and infrastructure for alternative mobility.