London, Jakarta, Rome, Mumbai, Naples, New York, Boston, Beijing, Tokyo, Oslo. What do all these cities have in common? Much and little at the same time. In spite of some common traits, such as the presence of public space, mobility, water and garbage systems, parks, or governing bodies, these cities differ incredibly. Features such as their physical shape and their culture, or numbers like density and wealth seem incomparable. The question the arises, is comparison possible at all? It is legitimate to wonder whether comparing two or more urban areas even makes sense. To try to shed some light on this issue, besides logic reasoning, we can glance at how academia manages this problem.

First of all a sociological consideration: as two-thirds of the world population live in urban areas, finding local experts who talk about their city is rather easy. By consequence, it is clear that cities are not just aseptic objects but places where most of us live: there is an emotional component and attachment towards where we are formed or decide to live. Defending one’s own place and relative version of how a city functions can coincide with defending personal life decisions. From this tendency, a city-based knowledge might follow.

Let’s look at the discussion on whether electric scooters are good or not for our cities. Mobility sharing fleets arrived in Europe and the US in the last 3 years, following the same exact scheme. In some cities, it was a real success, while elsewhere a complete disaster. Drawing a single conclusion highly depends on the case we pick, while the truth lies in between: the same exact common sharing scheme fits well a city for specific peculiarities of that context, while not fitting another. While Mobike was successfully established in Florence, it completely failed a few kilometres south, in Rome. Technical features of the vehicle seem to be as relevant as the regulatory framework of the city, the commuting habits of its inhabitants, climate, and geography of the place. As there are so many variables, how can we understand differences and manage to compare cities? Let’s look at some examples from academia.

Main pitfalls of comparing cities

Comparing cities is made more complicated by the many disciplines and factors at stake. For the sake of simplicity, let’s look at political economy and urban politics, two fields where the high variety of socio-economic and geographic factors influence the analysis. Historically, there have been a number of competing visions of what cities key traits are and how they work (Park and Burgess, 1925; Dahl; 1967; Wirth, 1969; Jacobs; 1969; 1984; Saunders, 1983; Rae, 2004). Kantor et al (2005) suggest that there are common pitfalls that make comparative analysis deceitful:

- The lack of a common framework. There is not one theory or framework considered by academia as an indisputable pillar to study and compare different cities. A valid exception to this is in the field of Urban Economics, where the city model of Brueckner is commonly accepted as the main framework to compare cities and regions (2011).

- The ‘depth versus scope’ problem. Some scholars only dig into the idiosyncrasy of few case studies. On the other extreme there is superficial research comparing many cases.

- Contextual features. The urban contexts embrace the historical, cultural, geographic and demographic content of cities. This problem arises typically when many different cultures are encompassed in the analysis.

- Conceptual parochialism. The same concept has not the same meaning in all the cases we compare. A concept like decentralization has not the same meaning in France or the United States. Its meaning also varied across time. There are concepts highly dependent on the context.

Without a common ground, comparative research resembles a list of compendiums and monographs in different cities. The solution proposed by Kantor et al is twofold. On the one hand, deconstructing and being aware of the pitfalls is the first step. Secondly, the analysis should build upon a common framework based on categories, typologies, and variables that are defined beforehand to avoid the four pitfalls. A good example that follows this proposal is a framework constructed by Digaetano and Strom (2003) to confront urban regimes in different cities.

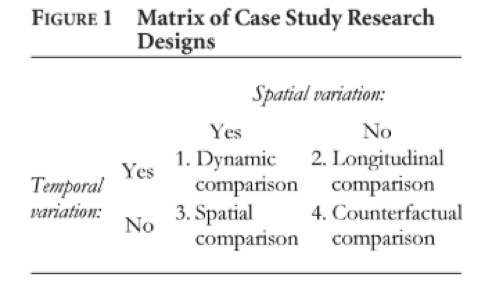

These five modes of governance, of course, are ideal types (see Weber 1962) and rarely if ever exist in pure forms. Powerful integration to build up a framework to look at a common object, which in this case is the institutional settings of a city, is to use a template that defines when and where the comparison among cities occurs. Gerring and McDermott propose a case study template to have a quasi-experimental grid to compare cities. Namely, they build-up four typologies identified through the question “is the comparison happening with a spatial or temporal variation?”.

A fair conclusion

Without some kind of theoretical construct that highlights common properties shared by cities, the comparative analysis makes little sense. Comparing cities is tempting, but it is complicated. This reflects the same complex nature of urban areas, which are special places exactly because of their social, economic, cultural density and diversity. Comparative analysis should be made on common grounds, rather than being based on a number of ‘theories of the middle range’, as Merton calls them (1968). Otherwise, understanding whether a mobility sharing scheme will work is just speculation.

The “urban” is not defined in the same way by all fields and authors. What is a city and what are the boundaries of geographical, administrative, cultural demarcation? Nor is a unique methodological approach shared. So, should we still compare then? Yes.

Keeping Emile Durkheim’s dictum in mind, science begins with a comparison. By comparing and measuring relationships, a knowledge with greater certainty can be achieved. (Kantor, 2005). Different urban disciplines such as urban economics, urban politics, urban sociology, urban geography, law and so on can’t be self-standing, as they describe a different aspect of the same urban global phenomenon. By the same token, cities are not self-standing, they are points of a ‘Global Network’ (Dematteis 1994) where informative flows are growing exponentially (Castells 1989).

Groups of computer scientists and physicists like those of the laboratory directed by Michael Batty at the University College of London aim at creating a new science of the city. Formal models and higher data quality will add explanatory power, however, the complex nature of the city won’t allow for the existence of one single science or theory. Recognition of diversity, tolerance, and dialogue can bridge different fields building up more solid frameworks to compare different cities. City practitioners can use this knowledge to make a change.

Bibliography

Brueckner, J. K. (2011). Lectures on urban economics. MIT Press.

Castells M. (1989) The Informational City, Information Technology, Economic Restructuring, and Urban-Regional Process. Oxford: Basil Blackwell

Dahl, R. (1967) The city in the future democracy. American Political Science Review LXI.4, 953–70.

Dematteis Giuseppe (1994). Global Network, Local Cities. In: Flux, n°15, 1994. pp. 17-23;

Di Gaetano, A., & Strom, E. (2003). Comparative urban governance: An integrated approach. Urban affairs review, 38(3), 356-395

Durkheim, E. (1982) The rules of sociological method and selected texts on sociology and its method. The Free Press, New York, NY.

Gerring J. et al (2007). An experimental template for Case Study Research.

American Journal of Political Science, Vol. 51, No. 3, July 2007, Pp. 688–701.

Jacobs, J. (1969) The political economy of cities. Random House, New York. (1984) Cities and the wealth of nations. Random House, New York.

Kantor P. and H.V. Savitich (2005). How to Study Comparative Urban Development Politics: A Research Note. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research. Vo 29.1, March 2005 135-51.

Merton, R. (1968) Social theory and social structure. The Free Press, New York, NY.

Park, R. and E. Burgess (1925) The city. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, IL.

Saunders, P. (1983) Urban politics. Hutchinson & Co, London.

Rae, D. (2004) The city. Yale University Press, New Haven, Connecticut.

Weber, M. 1962. Basic concepts in sociology, trans. H. P. Secher. New York: Citadel.

Wirth, L. (1969) Urbanism as a way of life: the city and contemporary civilization. In R. Sennett (ed.), Classic essays on the culture of cities, Appleton-Century-Crofts, NY.